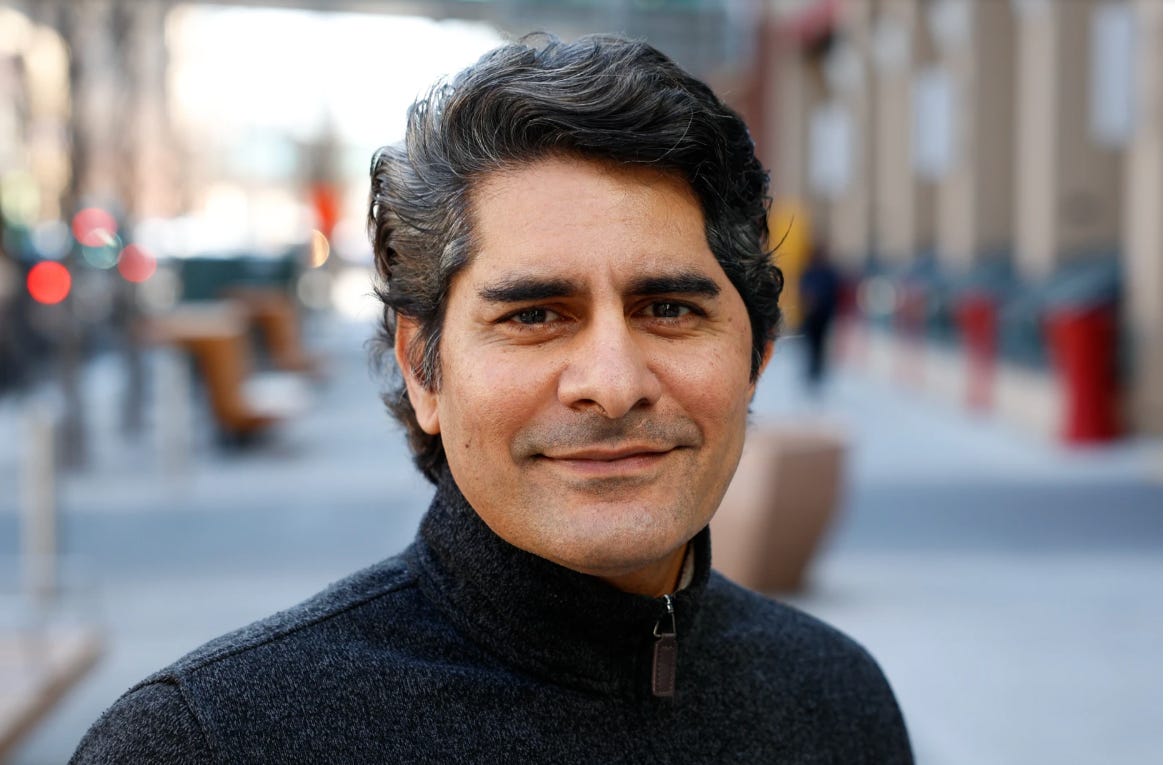

A Conversation with Dr. Bobby Mukkamala

Surgeon and AMA president tells us how his brain tumor diagnosis and community activism shape his plan to fix U.S. healthcare

If you drive up Interstate 475 into Flint, Michigan, billboards alternate between two realities. One touts the city’s enduring grit—“Home of the Vehicle City, Birthplace of GM.” The next warns of lingering lead in the water supply. That tension—pride and crisis, resilience and neglect—frames nearly every story that comes out of Flint. It has also deeply shaped the life of Dr. Bobby Mukkamala.

Over the past quarter‑century, Mukkamala has become many things at once: a meticulous ear‑nose‑throat surgeon, the owner of a private practice, a car collector that showcases his collection for charitable causes, a community organizer advocating for the many children harmed by the water crisis, and—most recently—the president‑elect of the American Medical Association. Then, last fall, he added an unexpected title: brain‑tumor patient. And, as he’ll tell us, it’s this mosaic of experiences that has best prepared him to lead the AMA through medicine’s next chapter.

The Stroke that Wasn’t

Last November, while briefing an AMA minority‑affairs section in Orlando, Mukkamala suddenly lost the thread of his remarks. To most audiences it would have registered as a minor stumble. He had experienced similar episodes before but had attributed these speech errors to aging. But this crowd—physicians who had heard him for a decade—knew the cadence and eloquence of his voice. They saw something was off.

Within minutes a text reached his wife: We think Bobby just had a stroke.

Although an initial ER visit was reassuring, Bobby went home to Flint knowing he needed to further evaluate his symptoms. There, his colleague arranged for him to obtain an MRI when he returned. Alone with the MRI technician at 9pm, he waited for the images to be burned to a CD (in the era of cloud computing and AI, we still use CD-ROMs and fax machines in medicine…sigh). The burner wasn’t working so he took out his phone to take pictures. And then he saw it: a “big-ass tumor in my left temporal lobe.”

He quickly convened his parents, wife, and kids to tell them what he had just discovered. While his reaction was decidedly Spockian (“I just needed to figure out the next step”), his family was understandably shocked and upset. In retrospect, he wishes at the time he was more attuned to their reactions rather than his own need to generate a plan. “I should have been more acknowledging of what they were going through as opposed to what I wanted to see done. And that's a lesson learned.”

Fortunately, his surgery (which was able to remove about 90% of the tumor) and subsequent treatments went forward without a hitch, allowing Bobby to assume his leadership at the AMA as scheduled. When I asked him what stood out to him from his experience as a patient, his answer surprised me. He said that his diagnosis led to “some of the best moments in my life…there was this phenomenal expression of love…and that was just amazing.” It made him realize that his usual way of sequestering expressions of appreciation and love for special occasions no longer made any sense. “I wasn’t going to hide my emotions any more..And so the glass was definitely half full from that point on, as opposed to half empty.”

On being a doctor, now

I was deeply curious about how Bobby’s approach to doctoring had changed as a result of his experience as a patient. He first mentioned that he now understood the role of support as medicine. When he was at medical appointments, “my mom, my dad, both of my kids and my wife, were all in every single room taking notes and interacting with [all my doctors]..that was a phenomenal experience…And yet here I am not doing anything to encourage that experience in my own practice.” It turns out, there’s science behind this as well. A meta‑analysis found that cancer patients with strong perceived social support networks have a 25% decrease in relative risk for mortality compared to those without.

Now he asks patients “Do you want to call anybody? Do you want to put anybody on a video call? I know you might be by yourself, but have you got any family out of town that wants to participate in this visit? This is important to ask because the shock of being the patient that gets told they have cancer eliminates the ability to just understand the facts.”

This is something I’ve learned as well - always bring a friend with a pen.

Another area that has taken on profound new meaning is his concept of risk. As surgeons, discussing potential complications is a crucial part of informed consent; we routinely present statistics to quantify the likelihood of certain outcomes. But there’s a deep cognitive and emotional dissonance between hearing about low frequency risks and actually internalizing them. Bobby agreed, saying, “the numbers are the numbers, but conveying those numbers, I think I will do differently…It's not something that can be just mentioned as a statistic or a fact without acknowledging the emotional response.” Think about it - Whether a risk is presented as 1% or 15%, the visceral reaction is often nearly identical—a gut-wrenching sense of vulnerability. It’s doubly uncomfortable perhaps because, outside healthcare, we typically retain some agency to mitigate or manage risk. In medicine, however, that control largely disappears, and patients must rely almost solely on trust. That’s why Bobby now sees risk communication not as a box to check, but as a sacred exchange—one that requires empathy, attention, and honesty.

On his view of our healthcare system

When I asked him to reflect on his sense of the healthcare system from the patient perspective, he started with an acknowledgement of how his healthcare was so different from what most Americans experience, a reality he desperately wants to help change. “I got an MRI scan within hours of needing it. And then I got all these consultations with a few different opinions and then me picking who I got along with best, who aligned with my goals, etc..

But if I lived in the house that's next to me, I would still be waiting…I wouldn't have had my surgery yet, let alone an MRI scan, or a consultation…the standard experience is waiting a while for an MRI scan prior authorization.”

“And so when I think about our country and what we spend on healthcare and where we rank [compared to other countries] as it relates to healthcare [for common conditions]…We're at the bottom of that list. We do an amazing job with brain cancer, but for people that have hypertension or diabetes…Those are the people that are the most disadvantaged. Or consider A pregnant person on the South side of Chicago… What they have to do to get obstetric care is get on a bus and go to the loop, which is where most of the OB-GYN care is located…I mean, there's so many headwinds as it relates to health care that I've learned a lot about with this experience. And it informs me better as I'm about to become president of the American Medical Association to have both a lifelong experience as a physician and then in the last six months that of a patient… I think it’s just wonderful prep to advocate for patient care and advocating for physicians role in that patient care.”

On calling Flint Home

When Dr. Mukkamala and his wife were deciding on where to establish themselves after medical training, they debated between returning home to Flint or staying in a big city like Chicago. A big part of their decision was his personal connection to Flint having grown up there; his Dad was a radiologist and his mother a pediatrician who had done their residencies at Hurley hospital. Another reason was their desire to start a private practice. “I knew five physicians right on day one…So I had a few patients starting immediately as opposed to building it and waiting years for it to grow. We were both at full practice volume within a year. But I did tell my wife that look, we'll go to Flint. We've got our grandparents that are there to take care of our newborn kids, our twins. If you don't like it after a year, I'm happy to move back to Chicago and we'll practice there. And here we are 25 years later, still in Flint, Michigan. So it worked out well!”

Because of his lifelong ties to Flint, his role as past chair on the Community Foundation of Greater Flint and and current role as a board member of the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, Bobby found himself squarely in the middle of the lead water crisis from contaminated pipes that made national news. As he explained in his recent inauguration speech, “Post-industrial Flint [has] incredible and heartbreaking health disparities,” and that was before the lead water crisis. He specifically highlighted the city's deep struggles, stemming from widespread poverty and lack of community investment all contributing to elevated rates of obesity, chronic illness, cancers and alarming levels of infant and maternal mortality.

Fortunately, there were “ a lot of contributions that came from around the country and the world to help manage the lead crisis.” Instead of focusing on creating complicating rules for who to help, “We said, you know what? These are kids who are challenged anyway…There are so many headwinds when you grow up in Flint. And now another headwind is lead exposure. Let's use these contributions to monitor and help them with their education [and healthcare] from now until they're 18 years of age…we’ve now replaced 90 some percent of our lead pipes while creating resources and programs to help these kids. So it's come a nice way.”

I was also curious if he felt any hesitation to be so outspoken during the crisis, given that he was not a trained expert in toxicology and/or child development. He remarked “You don't need an otolaryngology residency to talk about this, right? You just need a basic science medical school training to explain to people what lead does.” He added

“this community, this country has been so amazing to my parents and their generation that the least I could do is leave it better than I found it, right? To help move us a little more forward, just like my parents helped this community as well.”

Ultimately, Bobby's commitment underscores how leadership in a crisis transcends professional labels—it's fundamentally about responsibility, compassion, and paying forward the opportunities we've been given.

On his focus for the AMA

Dr. Mukkamala has a lot on his mind as he starts his term as President of the AMA. One area is access to care. He recounts that when he first started his practice, he might see one patient a month who was referred from an urgent care clinic. Now, he may see up to a dozen patients a day from urgent care, often with the wrong diagnosis. And it’s simply because there are not enough primary care doctors to satisfy the demand. Furthermore, he notes that we have a looming physician shortage that will only compound these problems. “We don't have enough physicians because the narrow part of that funnel is the residency position, right? Graduate medical education is not funded nearly enough to keep up with the demand. The number of residency slots got frozen in the nineties. And here we are 30 years later with a very similar number of residency positions.”

This shortage leads to less time with patients. And because primary care has relatively poor reimbursement, this means PCPs have to see even more patients quickly to keep the lights on. Reflecting on the reimbursement from Medicare (which sets a benchmark that commercial payors negotiate around), Bobby said “the other interesting thing is that the path that payment to physicians goes through is totally different than what payment to hospitals go through… If a hospital's cost goes up by 1.2%, they automatically get 1.2% more the next year. It always keeps up. Our costs [in private practice] have gone up by almost 30% in the past 20 years, and yet our payment rate has gone up by only a few percent. So this is actually a drop in reimbursement…that needs to change. And even something as simple as saying…just like hospitals, if the cost to take care of a patient in your office goes up by 1.2%, we will increase our reimbursement by 1.2%.”

Witnessing the reimbursement battle from my academic perch—largely insulated from day-to-day payor negotiations—was a wake-up call. It underscored how the AMA must speak for all physicians, especially those in private practice who often anchor their communities’ health. The headaches we all share—mounting paperwork, relentless prior-auths, ever-shifting compliance rules—hit independents even harder, because every extra hour and dollar comes straight out of their own emotional and professional margins. Although private-practice doctors still account for roughly 40 percent of the workforce (down from 60 percent in 2012), they remain indispensable to access and continuity of care. Their struggle is our struggle, and rallying behind Bobby Mukkamala’s push for fair payment and reduced red tape is a fight every physician should cheer. (Some good reading here and here)

Ultimately, Bobby wants to use improved reimbursement to keep people out of the hospital. “I don't want [society] to pay better for when somebody has a heart attack and pay worse for the prevention of that heart attack.

And how can we prevent the heart attack? We should have a 20 minute conversation instead of a five minute conversation with somebody in the office about their pre-diabetes, about their hypertension, about their lack of exercise that prevents disease. And right now that pays like crap relative to when they get that disease.”

Here, Bobby walks the walk. He feels so strongly about preventive health counseling that he got board certified in lifestyle medicine (in fact, he remarkably took and passed the test a week after getting his brain tumor diagnosis). I think that's critical to prevent disease. And I think that's where I would like to see us put more focus instead of having to go through congressional battles about having another 2.7% decrease in Medicare payment, when the real way to take better care of patients is to keep that payment up with our cost of doing that work… that's the goal.”

I wanted to also get a sense of the congressional temperature when it came to these issues in health care. Surely, I imagined, there are many in Congress that deeply care about the health of the nation on a bipartisan basis. Bobby told me that’s generally true, but that there are so many competing priorities that healthcare is currently on the political back foot. He noted that we all need to get involved to effect change. “We need to convince by saying - Look, our life expectancy in this country is stagnating because of a lack of investment in prevention of disease. Sure, we may protect the border. We may do X, Y, and Z on your list, but people are dying sooner than they should. Disease is not being detected as soon as it should. Prior authorization for the medicine we know is better is getting denied…These are all things that affect the quality of our health ...Health care should not take a backseat.”

On Burnout

Much ink has been spilled elsewhere on the prevalence and impact of burnout on the physician workforce but it's worth unpacking.. Physician burnout isn’t a granola wellness issue—it’s a job hazard with significant societal implications. Nearly half of U.S. doctors report burnout, almost twice the rate of other American workers, thanks to all the work we do and requirements we must meet that feel distant or even unrelated to patient care. Think of the Sisyphean slog of clunky EHRs and mindless compliance trainings. The consequences are dire: burnt out physicians make more mistakes, their patients fare worse, and satisfaction scores tank. The human cost is heartbreaking—about 300 physicians die by suicide each year, giving our profession a suicide rate well above the national average. The economic costs of this are also substantial. $4.6 billion a year is lost annually in turnover and lost clinical hours. Looked at from an organizational level, this translates to approximately $7600 per employed physician each year. All of this begs the question - Who safeguards the well-being of those who devote themselves to ours?

It turns out this is a high priority for Bobby and the AMA as he referenced in his inaugural address. In addition to the above aforementioned statistics, Bobby also highlights another seldom referenced point: the impact on access. “We have people that are 54 that a generation ago, before we had all this stuff to deal with, who would happily practice until age 75 or more because they loved practicing medicine so much…But now they’re thinking about retiring at age 60 because of all the hassles.” He acknowledges some of this burnout may be improving with technology like AI scribes, but also points out the current economic and functional realities of integrating these tools. “There's AI products you can buy that listen and then create and that's all good. But that has consequences also, right? The liability associated…What if it comes to the wrong conclusion? What if it types the wrong thing?” He also notes that these tools aren’t cheap yet! He wonders how practices can be expected to absorb these new technological costs “when we can barely keep up with the inflation of labor and practice management costs.” This is why Bobby is so focused on burnout and its root causes - left unaddressed, we’ll simply have less doctors, worse access, and worse outcomes.

On the AMA’s standing w MDs

When Dr. Mukkamala was recovering from his brain surgery, he decided to go online and survey doctor opinion on the AMA. “So I see there are so many negative opinions about the American Medical Association that are not founded in fact…But yet I know as a president-elect of this organization, all the things we've done yet people are very insulting of the AMA because they're just not aware.” I have to admit; I also was unaware of the breadth of things that the AMA does. While it is best known for its high-profile advocacy on Capitol Hill—lobbying Congress and CMS on Medicare payment reform and scope-of-practice bills and its stewardship of the JAMA journals, its influence runs much deeper. The AMA created and continually updates the CPT® code set that every public and private insurer uses to process claims. The revenue generated by work like this funds the AMA mission that includes programs like multimillion-dollar Reimagining Residency grants to modernize GME curricula. It also operates a Litigation Center that files or joins precedent-setting lawsuits when statutes or regulations threaten patient care . It also offers free resources for burnout-reduction playbooks and telehealth toolkits, publishes a Private Practice Playbook (contract templates, KPI dashboards), and hosts the Physician Innovation Network, pairing frontline doctors with health-tech start-ups. In addition, the AMA funds health equity initiatives that fund communities facing lack of health care access, food and housing insecurities, and widespread poverty. In short, while the AMA is the public face of medicine in Washington, it also supplies the coding infrastructure, legal muscle, education grants, and operational resources that many physicians use every day—often without realizing the source.

So I asked Bobby how he plans to address this understanding gap. He argues that part of it is getting the message out.”Every time I go somewhere and give a live presentation to a room of 50 people in South Dakota, or to a room of thousands of people in Washington, DC, there is almost unanimous commentary that I didn't know the AMA did that!” And that’s his plan. As president, he will “hit the road for the typical 200 plus days and have those interactions that hopefully motivate people to get involved with an organization that helps them take better care of their patients.”

On the threats to science

While the cuts to scientific funding have certainly been in the news, it’s easy to lose sight of this calamity given the constant incoming of current events. But make no mistake, these cuts are having a disastrous result. Since the Trump administration took office, the NIH has terminated over 2100 research grants totaling almost $10 billion and an additional $2.6 billion in contracts. These cuts have targeted myriad projects including vital studies on cancer, rare diseases, and public health preparedness.

The effects are not limited to blue states or “elite” universities. Red states such as Texas and others have seen hundreds of millions of dollars in research grants canceled, undermining local universities and health institutions that rely on federal funds for biomedical research and innovation. Between these cuts and our newfound hostility to immigrants, our world class talent pool may decamp the U.S. for countries with more stable research environments.

These cuts apply to global health as well. One important program caught in the crosshairs has been the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) started under the George W. Bush administration. This program has saved over 26 million lives since its inception and is one of the great public health triumphs in global history. Yet the program is at risk. One analysis calculated nearly 25,000 deaths if the program were only frozen for 8 wks and then resumed highlighting the life and death importance of these medicines to affected communities. Our commitment to science, people, and freedom have always been America’s undisputed strengths when it comes to biomedical innovation - why would we give that up?

This issue is personal for Dr. Mukkamala as well. “This NIH grants change couldn't be more important to me as a patient. And the reason is the pill that I take because I have grade two astrocytoma is something that was just approved in August of this past year. I talked to the professor, the pathologist that created this product and he couldn't have done it without NIH funding. It doesn't get any closer to me. And again, I'm just one person, but it's such a perfect example of why NIH funding is critical to have the health outcomes that we want. I'd be dying earlier if it were not for NIH funding. I guarantee it. And again, it's not about me. But you multiply that by our entire population and we fail even more in healthcare when we don't fund research appropriately.”

–

Bobby Mukkamala’s story reminds us that the divides we often draw in medicine— academic vs. private practice, bench science vs. bedside care—are, in reality, artificial. When an ENT surgeon from Flint becomes a brain-tumor patient, when the AMA president-elect struggles to comply with mandates and practice costs, and when lifesaving drugs depend on federal grants that can vanish with a budget vote, the through-line is clear: our fates are braided together. Whether we work in an academic tower, a rural clinic, or a Capitol-Hill hearing room, we doctors all share the same mandate—protect trust, cut the red tape that frustrates doctors and keeps patients waiting, and defend the scientific infrastructure that turns today’s innovations into tomorrow’s standard of care. Mukkamala’s year at the AMA will test how much progress one physician-leader can spark, but the larger test is ours as a community of healers: Do we have agency in defending our profession? Will we add our voices to these efforts? I think we do and we must.

Quick hits

Book recommendation

Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell

Most Important mentor

“My dad is a radiologist. He's retired. He used to be president of the Michigan state medical society and He was on a council at the American Medical Association as an IMG. That was almost unheard of, Right? And there's never been an Indian president of the American Medical Association until my inauguration comes up in June. And so people tell me congratulations as the first Indian president as if I accomplished something. My dad built the staircase. And I just happened to be on the top step of it because of the effort that he put in coming to this country at age 25, now almost being 80. It's because of his effort that I'm here.

On your legacy

I want my legacy to be motivating people to improve the world that they live in. Passive humanity is not something that appeals to me. I want to see people pursue what they love, whether that's painting a beautiful painting or whether that's improving people's health or whether that's being a wonderful parent. All of those things are equal in my book.

On running for Congress

Honestly, my two choices when I'm done are to run for Congress and be a publicly elected person. The other thing is I now have an alternate certification to teach. And we have a 4 % college readiness rate upon graduation from Flint community schools. 96 % have to take some remedial classes. So teaching math and science in our Flint community high school is something that is also on my list and honestly is higher on the list than being an elected representative dealing with the stuff that happens in Washington, DC. So that's where I'm headed.

Intro Music for a Documentary about you

—

Dr. Rohan Ramakrishna is a Professor of Neurosurgery at Weill Cornell Medicine and one of the founders of Roon. He started Roon with Vikram Bhaskaran and Arun Ranganathan because they believe that patients need trusted answers to their healthcare questions, anytime and anyplace.

Speaking of Roon, we’re expanding! We’re a place that celebrates medical expertise and would love to speak with great physicians everywhere!

You can Sign Up Here to be an expert creator on Roon. You can be either a health care provider or someone who has lived experience with the conditions we serve(in particular, looking for oncologists and OBGYNs) If you’re a physician selected to be on Roon, you will be part of an elite medical community and can expect a beautifully designed medical profile that highlights your expertise and compassion - all in service of educating your patients and the world.

Once you sign up, someone from our team will contact you to get you setup!

To leave you with a final thought: We think we need a Facebook community/support group for medical creators to share tips, ideas and opportunities with each other. If you’d like to join, add your name here. You don’t need to be a physician, btw! Anyone who describes their role as being a healer or medical communicator is welcome.

The name Good Medicine reflects many things, but importantly, It also pays homage to Bon Jovi’s classic “Bad Medicine.” To our readers who are fans of 80s rock, this one’s for you.